Homework at European integration: zero for banks and 4% for energy

The issue about Moldova’s integration within the European Union, which whirls around aligning the political, social, and economic standards of the community (not to mix up with the joining to the bloc) is a specific one. Supported by the Baltic advocates and Romania, as well as many other European governments, this desire of Moldovans took a concrete shape when the Association Agreement was signed in June 2014.

Almost two years since this historical event, one may find that Moldova has made a modest progress this way, the country having implemented, on average, little over 23% of the measures foreseen in the Association Agenda.

Political turbulences, high corruption, the institutional crisis and staff shortages have practically blocked Moldova’s efforts towards implementation of the Association Agreement with the E.U. The financial-banking sector tops the worst record in this regard – the progress there was zero.

Expectations and optimism

In general, according to the expectations of the Economy Ministry, Moldova’s integration within the Union had to generate the following benefits:

• Growth of the national revenue by 75 million euros a year during the mid-term and by 142 million euros a year during the long term;

• Growth of exports by 15% during the short term and by 16% during the long term, while imports should increase by 6% and 8% respectively;

• Decrease of consumption prices by 1% during the short term and by 1.3% during the long term;

• Generation of a more stable trade regime for DFI growth and enhanced competitiveness.

These expectations were confirmed by independent studies prepared by the think tanks Expert-Grup and IDIS Viitorul. Alexandru Oprunenco, expert at UNDP Moldova, says that the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the E.U. was a logic stem for Chișinău and aligns the rules of the World Trade Organizations, where Moldova is a full rights member. At the same time, leaderships in Brussels have repeatedly stated that Moldova was not a trade threat for the European Union; for Moldova however the E.U. becomes the biggest trade partner that provides for a range of benefits both in export and import.

The Association Agreement covers almost all the aspects of social-economic life in Moldova; at the regulatory level, a government decision coded #808 (and issued in October 2014) approves the National Actions Plan for Implementation of the Association Agreement (PNAA) during 2014-2016, which describes the concrete measures to be taken in each category.

The big challenge for Moldova is in fact the process of implementation of PNAA. The famous European policy ”More For More” should stimulate the changes from inside, but the Moldovan government did not push too much in order to achieve those changes – neither at the quantitative level nor at the qualitative level.

Less than 25% of measures achieved

In this context, Prime Minister Pavel Filip admitted in February 2016 that the Association Agreement had been implemented at 60-63%, according to official figures, and that “the special commission that oversees this process had not met since the summer of 2015 because of the political crisis.”

Meanwhile the Euromonitor report that is being published by think tanks Expert-Grup and ADEPT says that only 24% of activities were fulfilled out of the total 407 during August-December 2015; another 29% was unfulfilled and 35% was in progress.

For certain strategic areas such as food safety, financial services and energy – in spite of activities in progress – the bad news is that the shortcomings relate to the categories that are most important for those areas.

For example, the objective related to writing and enforcing a new law on money laundering prevention and terrorism finance remains unfulfilled in the context of the implication of a Moldovan bank in the notorious money laundering scheme between Russia and the E.U., known as Laundromat. Given the unstable banking sector in Moldova, one might blame the lack of political will or clear vision over the situation for the lack of tougher legislation.

Another objective which was due in 2015 and which Moldova failed concerns the capacity building in the public finance management. The functionaries of the central and local public authorities that take part in the management of public money did not receive a mechanism of professional training. This activity transfers to year 2016 and thus puts further pressures onto the whole implementation process.

In the case of the National Food Safety Agency (ANSA), the most important arrears are related to the weak institutional capacity in food safety control and the troubles about the conformity of animal products to the E.U. safety norms – except for eggs, honey, and caviar. Furthermore, ANSA does not have powers to contribute legislation on food safety.

In the energy sector, a set of European directives is late for integration into the national laws. Eleven documents of this kind are late and the National Plan on Energy Efficiency for 2016-2018 – which was already due – does not exist yet.

Former Foreign Minister Iulian Groza, who is currently an expert at the European Policy and Reforms Institute, says that the arrears to PNAA endanger the capitalization of the advantages which are provided by the Association Agreement, especially those related to trade and export quotas. Also, the functioning of enterprises in breakaway Transnistria may be harmed, because the Agreement lacks a practical mechanism of implementation of that region.

Furthermore, take the judiciary reform in Moldova, which is a crucial objective to heal the business environment – out of nine activities only three have been fulfilled and the rest are still being implemented. One important achievement is the adoption of a Mediation Law (#137) and approval of the Ethics and Professional Conduct Code for Judges. On the opposite side, a number of measures are late: construction of a Justice Palace; judiciary police reform; prosecution service reform; reorganization of the National Integrity Commission; and a whole Justice Reform Strategy is missing.

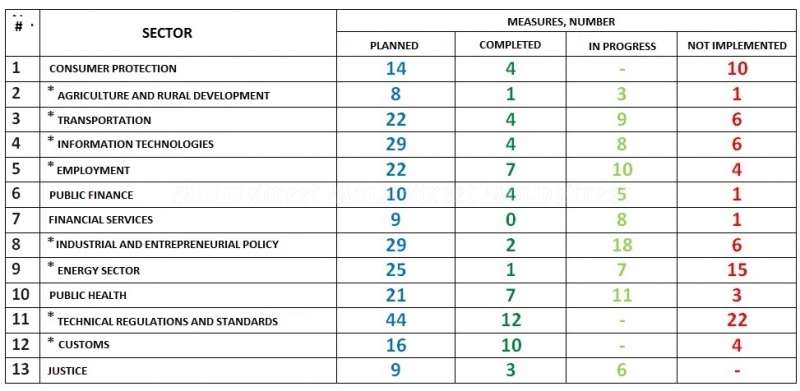

In statistical terms, the measures implemented during August-December 2015 in the most relevant economic areas look as follow:

* measures which are considered ”Fulfilled in part” have been omitted in this table.

Banking sector – zero progress

None of the areas included in the document excelled more than 65% in implementation and just one economic-related area – customs – achieved more than 60% (62.5%). The average rate of implementation of the measures as laid out in the Association Agreement is 23.2% per most important social-economic areas. The sectors where the implementation rate is lowest were in fact the most problematic ones and made headlines in connection with high profile corruption or grave violations: the banking sector registered zero progress, the energy sector obtained just 4%, and agriculture 12.5%.

The graphic below shows the situation in the most relevant areas and the status of measures, in %.

Institutional deficiencies

Representatives of the Agriculture Ministry told Mold-Street.com that the pressure of these measures delays the institutional efficiency at a great extent and from the procedural point of view the writing of the Preliminary Regulatory Impact Analysis slows down this process even worse. There is also a sharp shortage of personnel and training new employees become a new operational management burden.

Although the Government’s ambitions are high, they are likely to remain as such. The roadmap regarding the Priority Reforms Agenda that needs to be implemented by July 31, 2016 names the months of March through May as deadlines for the settlement of the above-named deficiencies. In March, for example, the Parliament had to pass a financial legislation that was coordinated with the World Bank and the Monetary International Fund. Also then the National Bank of Moldova needed to work out an action plan for enforcement of the Financial Sector Assessment Program. Again, March is the time when the cabinet had to issue a roadmap for implementation of the DCFTA on the entire territory of Moldova and upgrading coordination between the executive and legislative branches of government in order to ease the efforts of harmonizing the national legislation with the commitments assumed in the Association Agreement and the DCFTA.

Later, in April or May, the Economy Ministry needs to submit a secondary legislation afferent to the Association Agreement on metrology and standards.

At the second meeting of the E.U.-Moldova Association Council on March 14, 2016, in Brussels, the Moldovan side tried to persuade the European Commission to give it a new chance to implement the Association Agenda measures.

E.U. High Representative Federica Mogherini told journalists after the meeting that the E.U. would continue supporting the reform program in Moldova and that the sides shared a common point of view regarding the concrete actions and outcomes. She underlined that “there is a common desire to enter the phase with the delivery of the products of common work,” upon which the E.U. financial aid depends.

Risks of compromising the Association Agreement

The head of the E.U. Delegation to Moldova, Pirkka Tapiola, was quoted as saying earlier that corruption and the decaying status of the judiciary were the main constraints in the way of obtaining the benefits of the Association Agreement; these sectors represented a “negative example” for delayed implementation of the Association Agreement and propagated over the other areas. And here a major risk can be spotted: the arrears have started overlaying with the measures planned to complete in January-June 2016; this fact puts in jeopardy the objectives which both sides hoped to see achieved in compliances with PNAA.

Given the lack of transparency in public affairs and the poor coordination between the government institutions – and these problems had existed even before the Association Agreement got signed – plus the lack of international support and of trust from society, the day when Moldovan citizens will start benefiting from the advantages of the Association Agreement looks even more distant.

* * *

This material was produced as part of the project "Investigative business journalism for transparency and European integration,” which Business News Service (Mold-Street.com) is implementing with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The opinions expressed therein belong to their authors and do not reflect necessarily the stance of NED or the U.S. Government.